INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor and the leading cause of carcinoma deaths in women, with more than 2,088,849 new cases occurring worldwide annually.”

The progression of breast cancer follows a complex multistep process that depends on various exogenous (diet and breast irradiation) and endogenous factors (age, hormonal imbalances, proliferative lesions and family history of breast cancer).”

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a key point in the progression of cancer metastasis. EMT is a critical process in which epithelial cells lose their apical basal polarity, cell-cell contacts and transdifferentiate into fibroblastic migratory cells with mesenchymal characteristics. EMT is also involved in intravasation, progression of tumor cells and particularly during invasion when tumor cells migrate to distant organs to form metastases.

Vimentin overexpression in cancer is associated with tumor growth and metastasis, however more research would be crucial to evaluate its specific role in cancer. Its overexpression in many epithelial carcinoma, may act as a potential target for cancer therapy.”

Therefore, the aim of our present study is to determine the expression of vimentin in breast carcinoma and correlate it with prognostic and predictive markers such as age, tumor size, histologic type and grade, lymph node status, lymphovascular invasion, ER-PR-Her2neu marker status and Nottingham Prognostic Index.

MATERIALAND METHODS

Sixty patients of breast carcinoma in whom mastectomy was performed and a diagnosis of invasive duct carcinoma was made on histopathological examination, were recruited in this study aftes proper written consent from the patients.

All received specimens were properly labelled mastectomy specimens, well preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin, sent with patient’s history and proper clinical details on the requisition form.

Relevant clinical data with regard to sociodemographic variables, clinical history including family history and radiological findings were obtained.

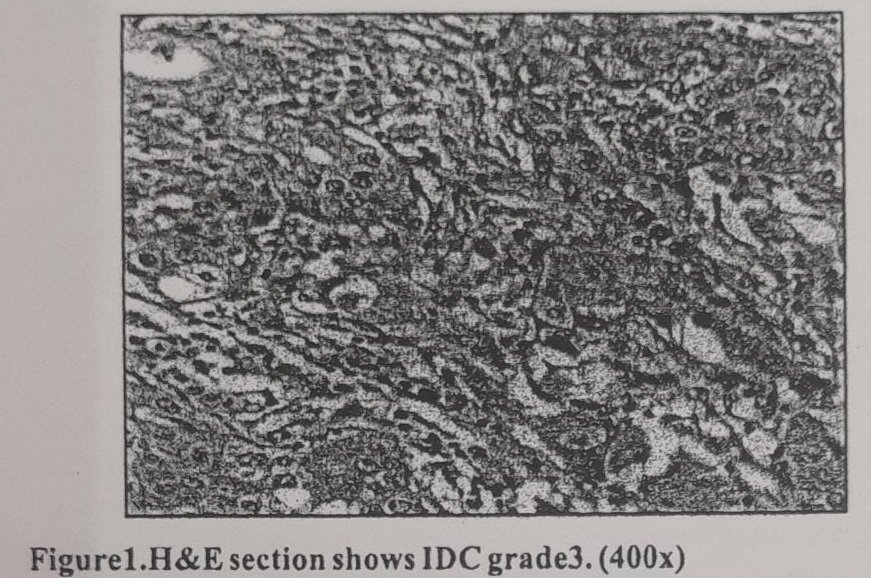

Following adequate fixation for about 12-24 hours, the representative tissue sections were submitted for routine processing and paraffin embedded serial sections of 3-4 micron thickness, were obtained. These were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin stain for routine histopathological examination and immunohistochemistry was applied thereafter.

In our study we used vimentin as the primary immunohistochemical marker. ER, PR and Her2-neu expression of the cases was also recorded.

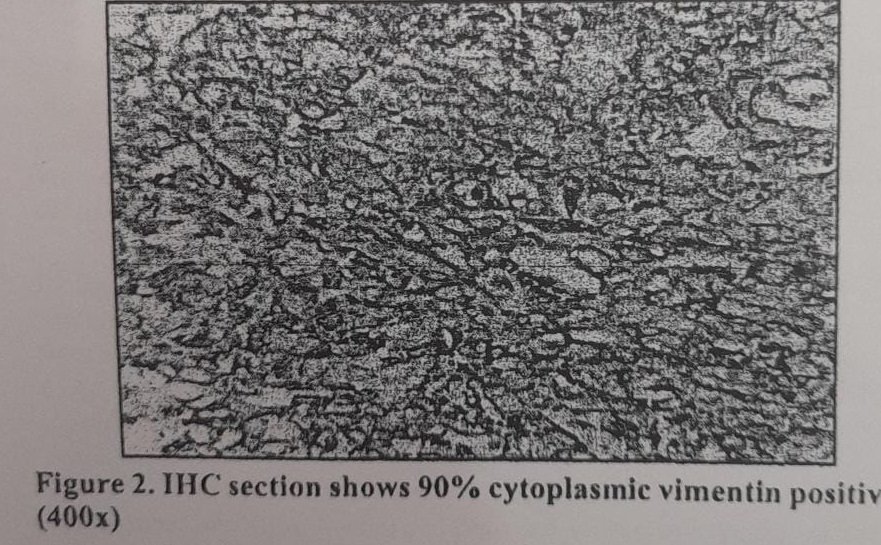

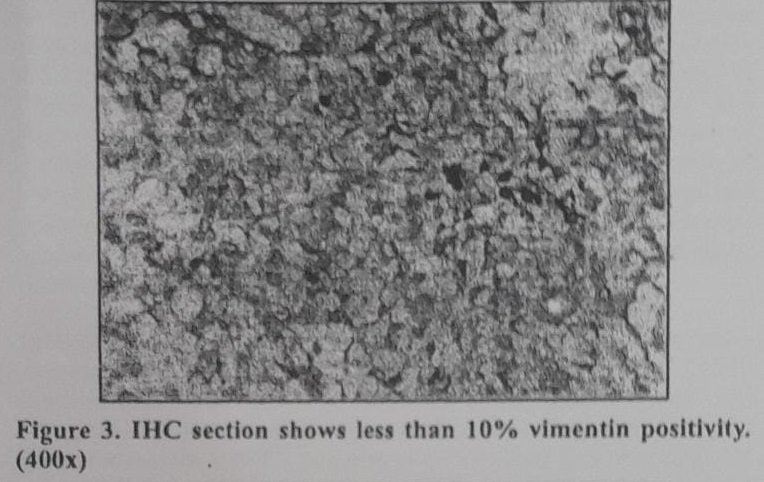

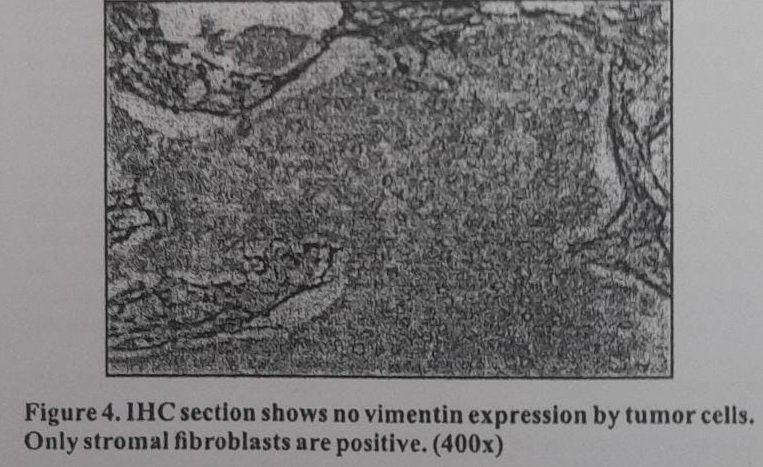

Assessment of Vimentin

Vimentin is expressed as distinct cytoplasmic granular positivity. Five hundred cells were counted in an area of maximum vimentin positivity and score of >10% was considered as significant. Less than 10% staining is taken as negative. Stromal cells expressing vimentin served as internal control.

Nottingham prognostic index

Nottingham prognostic index (NPI) employs a three-tiered classification system that stratifies patient with breast cancer with good, moderate and poor prognostic groups.

The index is formulated by including three independent prognostic factors that include tumor size, lymph node status and histologic grade. NPI is calculated as NPI-0.2 x Tumor size (cm) + Lymph node stage (1/II/III)+ Tumor grade (1/2/3). For Lymph nodal stage, a score of 1 depicts no nodal involvement. A score of 2 denotes involvement of three or less axillary lymph nodes or single internal mammary lymph node while a score of 3 is given for involvement of 4 or more axillary or presence of both internal mammary and axillary lymph node involvement. This calculated NPI is classified as low (NPI<3.4, group A), intermediate (NPI 3.4-5.4, group B) and high (NPI >5.4, group C). NPI is a widely used integrated prognostic variable in patients with breast cancer.

DATA ENTRY AND STATISTICALANALYSIS

The collected data were transformed into variables, coded and entered in microsoft excel. Data were analyzed and statistically evaluated using SPSS-PC-17 version. Qualitative data has been presented in the form of frequency and percentage/ proportion. Significance of difference has been calculated using Chi-square / Fisher’s exact test and Mann Whitney U test. P value less than 0.05 will be taken as significant.

RESULTS

This study was performed on 60 patients who were diagnosed as having invasive breast carcinoma. Majority of the cases were in the age group of 35-44years. Youngest patient in study was 24 years old and the oldest was 87 years.

Twenty six (43.3%) cases were of histological grade 3, 22 (36.7%) cases were of histological grade 2 and 12 (20%) cases were of histological grade 1.

Lymphvascular invasion was present in 19 (31.7%) cases while it was absent in 41 (68.3%) cases.

Majority of cases 44 (73.4%) belonged to T2 stage, while 8 (13.3%) belonged to both T1 and T3 stage.

Most of the cases 35 (58.3%) were in stage NO, 16 (26.7%) were in N1, 5(8.3%) were in stage N3 and 4 (6.7%) were in stage N2.

Thirty one (51.7%) cases showed ER positivity while 29 (48.3%) showed negative ER expression.

Progesterone receptor negativity was seen in 31 (51.7%) cases and progesterone receptor positivity in 29 (48.3%) cases.

Her-2-neu overexpression was seen in 6 (10%) cases while negative Her-2-neu expression was seen in 40 (66.7%) cases. Fourteen (23.3%) cases were equivocal for Her2neu expression.

Thirty five (58.3%) cases belonged to non triple negative group while 25 (41.7%) belonged to triple negative group.

In NPI, 37 (61.7%) cases were in category B of moderate prognosis, 14 (23.3%) cases were in category C of poor prognosis and remaining 9(15%) were in category A of good prognosis.

Twenty seven (45%) cases were positive for vimentin, 33 (55%) cases showed vimentin negativity.

Most common age group showing negative vimentin expression was 35-44 years. Maximum number of vimentin positive cases were seen in age group 55-64 years.

For histological grade3, vimentin positive group 22(84.6%) cases, 4 (18.2%) cases belonged to grade 2 and 1 (8.3%) case belonged to grade 1. In cases with negative vimentin expression, 4 (15.4%), 18 (81.8%) and 11 (91.7%) cases in the category of histological grade 3, 2 and 1 respectively.

Lymphovascular invasion was present in 14 (73.7%) cases and absent in 13 (31.7%) cases of the vimentin positive expression group. In cases with negative vimentin expression, lymphovascular invasion was seen only in 5 (26.3%) cases while it was absent in 28 (68.3%) cases.

There were 8 cases in T1 stage, out of which 7 (87.5%) were vimentin negative and 1(12.5%) was vimentin positive. Out of total 44 cases in T2 stage 23 (52.3%) cases showed no vimentin expression whereas 21 (47.7%) cases were positive for vimentin expression. A total of 8 cases were in T3 stage of which 5 (62.5%) were positive for vimentin and 3(37.5%) were negative.

Eighteen (51.4%) cases with negative vimentin expression whereas seventeen (48.6%) cases with positive vimentin expression were in NO stage. Only one (20%) case was found negative and four (80%) cases were positive in N, stage.

Vimentin expression was seen in 3(9.7%) of ER positive cases of invasive duct carcinoma and in 24(82.8%) cases of ER negative cases. Negative vimentin expression noted in 28 (90.3%) of ER positive cases and 5(17.2%) of ER negative cases.

Vimentin expression was seen in 2(6.9%) of PR positive cases of invasive duct carcinoma and in 25(80.6%) cases of PR negative cases. Negative vimentin expression noted in 27(93.1%) of PR positive cases and 6(19.4%) of PR negative cases.

Vimentin expression was positive in 2 (33.3%) of Her-2-neu positive cases of invasive duct carcinoma, 20 (50%) of Her-2-neu negative cases, and 5 (35.7%) of Her-2-neu equivocal cases. Negative vimentin expression noted in 4 (66.7%) of Her-2-neu positive cases, 20 (50%) of Her-2-neu negative cases and 9 (64.3%) of Her-2- neu equivocal cases.

Vimentin was expressed in 5 (14.39%) of non triple negative cases of invasive duct carcinoma and in 22 (88%) of triple negative cases. Negative vimentin expression was observed in 30 (85.7%) of non triple negative cases and 3(12%) of triple negative cases.

In NPI there were a total of 9 patients in category A out of which 1 (11.1%) were vimentin positive. Category B had 37 patients in total with 17 (45.99%) showing vimentin positivity and the rest 20 ($4.1%) being vimentin negative. In category C, 9 (64.3%) showed vimentin positivity and 5 (35.7%) were vimentin negative.

DISCUSSIONS

In our study, 45% of the breast carcinoma cases showed vimentin positivity. This finding is consistent with the findings of other previous studies in which the range of vimentin expression varies between 45% and 57%. Majority of the researchers considered vimentin expression in at least 10% of tumor cells to be significant. Some studies Khillare et al’ and Elzamly et al” demonstrated higher percentage of vimentin positivity as they considered tumors to be vimentin positive irrespective of the percentage of cells ie., even <10%.

No significant correlation was found between vimentin expression and the patient’s age at presentation in our study. This finding is in accordance with the studies done by Hemalatha et al’ and Vora et al” which showed no association between the mean age of presentation and the vimentin expression. Similar results were obtained in various other studies performed by Niveditah et al” and Khillare et al. Contrary to this, Kusinska et al” found a significant correlation between age of the patient and vimentin expression in their study of 179 cases of breast cancer. They stated that women with vimentin positive cancers were significantly younger than vimentin negative ones. Another study of Yamashita et al” on 659 Japanese women was also found significant correlation (p value 0.016) between vimentin expression and age. The lack of a significant correlation in our study may be attributable to a smaller sample size as compared to studies which derived a significant correlation and had a larger study population.

In the present study, significant correlation was found between positive vimentin expression and the histological grade of the tumor (p value 0.001). Our findings were in accordance with the Kusinska et al”, Raymond et al”, Domagala et al”, Sheshadri et al”, Hemalatha et al’, and Korsching et al.” Khillare et al’ could not derive a significant correlation in between these two variables but he observed that increased vimentin expression was associated with high histological grade. A significant correlation with histological grade denoted higher expression of vimentin in poorly differentiated tumors compared to well differentiated and moderately differentiated tumors.

In the present study, significant correlation was found between vimentin expression and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (P value 0.005). These findings correlate with those of Khillare et al’ who obtained a significant positive correlation between the two variables. However, there have been studies by certain authors Wang et al” and Lakhtakia et al which showed no correlation between vimentin expression and lymphovascular invasion. Despite obtaining an insignificant p value, these authors observed LVI association with increased vimentin expression. A significant positive correlation of vimentin expression with lymphovascular invasion in our study reflects the fact that vimentin is expressed when there is epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Its increased expression denotes more chances of lymphovascular invasion (LVI), thus leading to widespread and aggressive disease.

In our study no significant correlation was found between vimentin expression and tumor size. This finding is in accordance with the studies done by Hemalatha et al’, Khillare et al, Kusinska et al” and Vora et al”. No significant correlation was also found by Yamashita et al” and Seshadri et al”.

In the present study, no significant correlation was found between vimentin expression and lymph node status (p value 0.108). This finding is in accordance to the study done by Hemalatha et al’, Khillare et al’ and Niveditha et al”. But Vora et al” and Wang et al” found significant correlation between high vimentin expression and lymph node positivity.

receptor status (p value 0.0001) in the present study. Increased vimentin expression in breast carcinomas seemed to be associated with ER negativity. This finding is in accordance with the findings of Seshadri et al”, Wang et al”, Khillare et al, Kusinska et al” and Raymond et al.” Vora et al” did not find significant correlation of vimentin with ER but they observed higher incidence of gain of vimentin with ER negative receptor status. ER negativity is associated with poor prognosis in terms of overall outcome as such tumors are not amenable to targeted therapy. High vimentin in such ER negative cases denotes dismal prognosis in vimentin overexpressing humors.

In the present study, negative correlation was found between vimentin expression and PR expression, significant p value was found (0.0001). Similar results were found by Kusinska et al”, Seshadri et al” and Wang et al. “Vora et al” and Khillare et al’ observed higher incidence of gain of vimentin with PR negative receptor status though they could not establish a significant correlation. We inferred that a high vimentin expression was associated with PR receptor negativity. Significant correlation of vimentin overexpression with PR negativity also denoted tumor aggressiveness and poorer prognosis due to the lack of responsiveness of such tumors to hormone treatment.

In our study, no significant correlation was found between vimentin expression and Her-2-neu expression (p value 0.660). Similar results were found by other researchers Vora et al”, Khillare et al’ and Wang et al.” However significant correlation was found by Kusinska et al” which may be attributed due to their large sample size. We may have not derived a correlation because of small sample size in our study.

We found negative correlation between triple negative cases and vimentin expression (p value <0.05). The findings of Khillare et al. Wang et al”, Yamashita et al” and Kusinska et al” were concordant with that of our study. Triple negative breast cancer patients are known to be of aggressive nature. The high vimentin expression in such patients points towards the fact that increased vimentin expression attributes to a poor prognosis.

Nottingham prognostic index (NPI) is well established widely used method for predicting survival of operable primary breast carcinoma cases. The present study showed significant correlation between vimentin expression and NPI (p value 0.039). Vora et al” observed that gain of vimentin expression associated with reduced relapse free and overall survival. However studies done by Hemalatha et al’ could not find significant correlation between NPI and vimentin expression. A significant correlation with NPI suggested that elevated vimentin expression in breast carcinoma reflected poor prognostic behaviour.

Vimentin expression is strongly associated with high histological grade, lymphovascular invasion, high NPI, negative ER/PR and triple negative status. We were not able to deduce any significant correlation of vimentin expression with the clinicopathological variables like age, tumor size, lymph node status and Her-2-neu status. Its expression is strongly associated with poor prognostic factors of invasive duct carcinoma.

Discovery of drug, WFA (WithaferinA) that binds and inhibits vimentin, can play a major role in preventing cancer cell growth. Researches are being done in this field, which will act as a milestone in treating breast cancer. It is thus emerging as a novel anti-cancer therapeutic target.”

We conclude that expression of vimentin is a potent indicator of biologically aggressive tumors. Its expression may serve as a potential target for cancer therapy in such tumors.

REFERENCES

1) Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer) Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

2) Fiegelson HS, Ross RK, Yu MC et al. Genetic susceptibility to cancer from exogenous and endogenous exposures. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1996:23:15-22.

3). Krieger N. Exposure, susceptibility and breast cancer risk: a hypothesis regarding exogenous carcinogens, breast tissue development and social gradients, including black /white differences, in breast cancer incidence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1989; 13 (3): 205-223.

4) Dickson RB, Lippman ME. Estrogenic regulation of growth and polypeptide growth factors secretion in human breast carcinoma. Endocr Rev. 1987;8(1):29-43

5) Thiery JP Epithelial mesenchymal transition in tumor progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(6):442-454

6) Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework Cell. 2006; 127 (4): 679-695. Negative correlation was found between vimentin expression and ER

7) Thalparambil IT, Bender L, Qanesh T et al. Withafarin A inhibits breast cancer invasion and metastasis at sub-cytotoxic doses by inducing vimentin disassembly and serine 56 phosphorylation. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(11):2744-2755.

8) Hemalatha A, Suresh TN, Harendra KM. Expression of vimentin in breast carcinoma, its correlation with Ki67 and other histopathological parameters. Indian J Cancer. 2013 ;50(3):189-194.

9). Khillare CD, Khandeparker SG, Joshi AR et al. Immunohistochemical Expression of Vimentin in Invasive Breast Carcinoma and Its Correlation with Clinicopathological Parameters. Niger Med J. 2019;60(1):17-21.

10). Elzamly S, Badri N, Padilla O et al. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition markers in breast cancer and pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer: Basic and Clin Res. 2018;8074.

11). Vora HH, Patel NA, Rajvik KN et al. Cytokeratin and vimentin expression in breast cancer. Int J of Biological Markers. 2009;24(1):p38-46.

12). Niveditha SR, Bajaj P. Vimentin expression in breast carcinomas. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46(4):579-584.

13). Kusinska RU, Kordek R, Pluciennik E et al. Does vimentin help to delineate the so called ‘basal type breast cancer? J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:118.

14). Yamashita N, Tokunaga E, Kitao H et al. Significance of the vimentin expression in triple negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(15):1056.

15). Raymond WA, Leong AS. Vimentin-A new prognostic parameter in breast cancer? J Pathol. 1989;158:107-114.

16). Domagala W, Lasota J, Dukowicz A et al. Vimentin expression appears to be associated with poor prognosis in node-negative ductal NOS breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1990; 137(6):1299-1304.

17). Seshadri R, Raymond WA, Leong AS et al. Vimentin expression is not associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1996;67(3):353-356.

18). Korsching E, Packeisen J, Liedtke C et al. The origin of vimentin expression in invasive breast cancer: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, myoepithelial histogenesis or histogenesis from progenitor cells with bilinear diffrentiation potential? J Pathol. 2005;206:451-457.

19). Wang H, Sang M, Geng C et al. MAGE-A is frequently expressed in triple negative breast cancer and associated with epithelial- mesenchymal-transition. Neoplasma. 2016;63(1):44-56.

20). Lakhtakia R, Alijarrah A, Furrukh M et al. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in metastatic Breast Cancer in Omani Women. Cancer Microenviron. 2017;10(1-3):25-37.