Introduction:

Endodontics is one of the fastest-growing disciplines in daily clinical practice (Chan et al, 2006). Root canal treatment is considered an essential element in the dental services provided to the population (Al- Omari, 2004). Nowadays, general dental practitioners (GDPs) are faced with a multitude of materials and techniques for such procedures, whilst dental schools consciously attempt to tailor their curricula towards evidence-based interventions (Chan et al, 2006). Several studies have revealed that the majority of dentists do not comply with the formulated guidelines for quality of root canal treatment. The majority of endodontic treatment is provided by the GDPs due to absence of specialists in endodontics and due to the lack of postgraduate programs (Al-Omari, 2004).

The purpose of the present study was, therefore, to investigate the attitude of dentists toward endodontic treatment and to explore the materials and methods employed by GDPS of Northern India and to compare these findings with well acknowledged international academic standards (Al-Omari, 2004).

Material and Methods:

A questionaire survey dealing with materials and techniques used in endodontic treatment was conducted among GDPS of North India. A two-part questionaire was mailed to 230 randomly selected GDPs mainly of Northern India. The first part requested basic information regarding age, year of qualification, field of practice, etc. The second part consisted of 35 questions on Endodontic practice and root canal treatment. Since the study was designed to explore the endodontic practice profile among GDPs, dental specialists and dentists with limited practice in any discipline were excluded.

Questions of Survey of endodontic practice by the general practitioners

1. Year of qualification

2. Are you a post-graduate?

[ ] Yes [ ] No3. Type of practice?

[ ] Private [ ] Government/hospital [ ] Others (please specify)4. Do you regularly treat (tick all those which apply)?

[ ] single-rooted endodontic cases [ ] multi-rooted endodontic cases [ ] re-treatment cases5. On the averange, how many root canal therapy do you perform per week? [ ]0-5 teeth [ ] 6-10 teeth [ ] 11-15 teeth [ ] 16-20 teeth [ ] 21 teeth or above

6. Are you satisfied with your current endodontic technique?

[ ] Yes [ ] No7. Do you feel that your dental schools training in endodontic therapy was adequate?

[ ]Yes [ ] No

QUESTIONAIRE

1. Do you take Pre-operative Radiograph?

[ ] Always [ ] Often

[ ] Occasionally [ ] Never2. Do you get the Consent form signed prior to the treatment?

[ ] Yes [ ] No3. Which technique of radiography you use?

[ ] Conventional [ ] Real-times images4. Do you check vitality of involved tooth?

[ ]Always [ ] Occasionally

[ ]Often [ ]Never5. How do you sterilize your endodontic files?

[ ]Autoclave [ ]Cold sterilization

6. Do you apply topical anaesthesia before injecting local anaesthesia?

[ ] Always [ ] Often

[ ] Occasionally [ ] Never

7. What gauge of needle do you use for injecting local Anaesthesia?

[ ] 18 mm [ ] 23 mm

[ ] 25 mm [ ] 27 mm

8. Do you use Rubber dam isolation?

[ ] Always [ ] Often

[ ] Occasionally [ ] Never9. Usual no. of visits to complete endodontic therapy?

[ ] Single [ ] Multiple

10. For Acute Pulpitis/Alveolar abscess ( emergency appointment) choice of treatment ?

[ ] Root canal opening with Analgesics & Antibiotics.

11. Do you use endodontic explorer for locating the canal?

[ ] Always [ ] Often

[ ] Occasionally [ ] Never

12. what kind of instruments you use for Endodotics?

[ ] Stainless [ ] NITI

13. Which method of instruments you use?

[ ] Hand instrument [ ] Rotary instruments

14. Do you use Golden mediums?

[ ] Yes [ ] No

15. Which is the 1″ Endodontic instrument you put in the canal?

[ ] Broach [ ] k file

[ ] H file [ ] Reamer

16. Do you use Apex Locator?

Always Occasionally

Often Never

17. What working distance you use from the Radiographic apex?

[ ] 1-2 mm [ ] 2-3 mm

[ ] 0.5 mm [ ] as far as apex

18. Do you use Open Dressing?

[ ] Always [ ] Occasionally

[ ] Often [ ] Never

19. Which method you use for cleaning and shaping?

[ ] Step back [ ] Conventional

[ ] Hybrid [ ] Crown-down

20. Do you use Magnifying lens or Operating Microscope?

[ ] Always [ ] Occasionally [ ] Often [ ] Never21. Which irrigant you use for root canal irrigation?

[ ] Sodium hypochlorite [ ] Chlorhexidiene [ ] Distilled water [ ] Hydrogen peroxide

[ ] Saline [ ] EDTA

22. What concentration of sodium Sodium hypochlorite you use for irrigation?

[ ] 2% [ ] 5% [ ] diluted

23. How many times you use Endodontic files?

[ ] single use [ ] many times

24. How you use Gates– Gliddern drill ?

[ ] Always [ ] Occasionally [ ] Often [ ] Never25. Which intra – appointment medicament you use between visits ?

[ ] Formocresol [ ] CMCP [ ] No medicament

26. Do you Infra – occlude the RCT treated tooth?

[ ] Yes [ ] No

27. Do you take master cone radiograph?

[ ] Always [ ] Occasionally

28. How many total radiograph you take for each case?

[ ] 2 [ ] 3 [ ] 4 [ ] none

29. Which temporary restorative material you use?

[ ] Cavit [ ] GIC [ ] Zinc-oxide

[ ] Eugenol [ ] IRM

30. Which root canal sealer do you use?

[ ] Calcium hydroxide(Base) [ ] Zinc oxide (Base)

[ ] Resin – based [ ] Any other

31. Which technique of Obturation do you perform ?

[ ] Lateral condensation [ ] any other

[ ] Vertical condensation

32. Which material you use for Post- obturation filling?

[ ] Amalgam [ ] Composite

[ ] Glass lonomer Cement [ ] Any other

33. When do you place the Post-obturation filling ?

[ ] Same day [ ] After 24 hr

[ ] After 7 hr [ ] None

34. Do you prescribe Antibiotics for patients undergoing Endodontics theraphy?

[ ] Always [ ] Occasionally [ ] Often [ ] Never35. How soon after Root canal therapy you advice Crown ?

[ ] 7 days [ ] 14day

[ ] 21 days [ ] None

Results:

Of the 230 questionnaires distributed, 152 completed replies were received, which is a 67% response rate. High response rate ensured that this study was representative for the general dental practitioners of the country.

Respondent and practice profile:

The distribution of the respondents according to the years of professional experience is shown in Table I. Years in practice were not evenly distributed amongst the total respondents. The number of the first two groups (0-5 and 6-10) consisted of more than half the total respondents due to the significant increase in the number of graduates in the last 10 years. The training backgrounds and practice profiles of the respondents are listed in Table II. Approximately 78% were in private practice and 22% worked in the government/ university sector, or for non-profit organizations. Fifty six percent respondents carried out five or less root canal procedures weekly.

Patient preparation:

Fifty two percent of the practitioners do not get the consent form signed prior to the treatment.

Vitality of the involved tooth is always checked by 24% followed by 70% of respondents which occasionally perform the vitality tests.

Forty eight percent practitioners occasionally applied topical anaesthesia before injecting the anaesthetic solution while 14% never use anesthetic injection prior to the procedure. Twenty five and twenty three gauge needles are equally common among the practitioners for injecting the anaesthetic solution (Table m).

Emergency appointment:

In case of acute pulpitis or acute alveolar abscess, the choice of treatment among the practioners (80%) is root canal opening with systemic antibiotics and analgesics, while only 20% prescribe the analgesics and antibiotics followed by root canal opening once the acute symptoms subside. About 10% practitioners give open dressing during all endodontic treatment cases, followed by 48% who occasionally practice it.

Table 1 : Data related to professional experience of the respondents.

| Professional experience in year | Percentage |

| 0-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 >20 | 29.25 21.4 17.8 11.8 19.75 |

Table 2 : The training background and practice profile of the respondents

Type of practice

Year of graduation :-

| Private (n) | Government/ Hospital/ Non-private organization | Total | |

| 1961-80 | 18 | 12 | 30 |

| 1981-2000 | 31 | 14 | 45 |

| 2001-10 | 69 | 8 | 77 |

Table 3 : Use of Anaesthesia

| Use of Topical Anaeshesia | % | Gauge of Needle | % |

| Always | 12 | 18 | 0 |

| Often | 26 | 23 | 42 |

| Occasionally | 48 | 25 | 48 |

| Never | 14 | 27 | 10 |

Table lV : Choice pf root canal irrigants and disinfectant intracanal-medication

| Choice of root canal irrigation solution | % | Concentration of NaOCI used | % | Use of Intracanal Medicament | % |

| NaOcl | 52 | 2% | 44 | Formocresol | 51 |

| Chlorhexidiene | 15.32 | 5% | Ca(OH)2 | 23 | |

| H2 O2 | 4.83 | Diluted | 28 | No medicament | 26 |

| Saline | 24.66 | 28 | |||

| EDTA | 3.16 | ||||

| Distilled Water | 2 |

Table V : Obturation technique and filling material

| Choice of Obturation Technique | Choice of Sealer | Choice of Temporary Filling Material |

| Technique | % | Type | % | Type of material | % |

| Cold lateral compacation | 91 | Ca(OH)2 base | 32 | Caviti | 27 |

| Vertical compaction | 5 | ZnOE base | 55 | ZnOE | 57 |

| Other | 4 | Resin-based | 13 | IRM(21) | 10 |

| Other | 0 | GIC | 6 |

Number of visits per endodontic treatment:

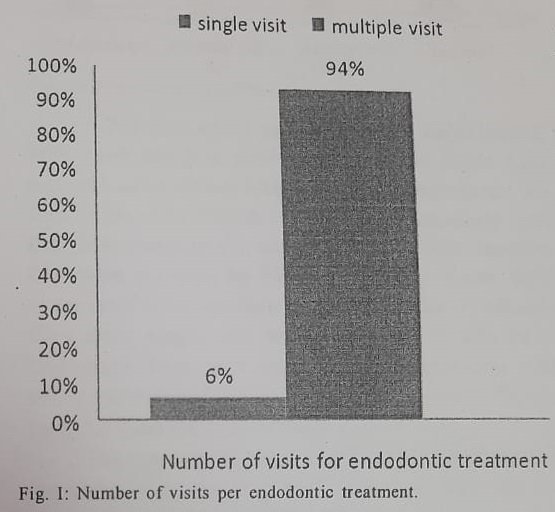

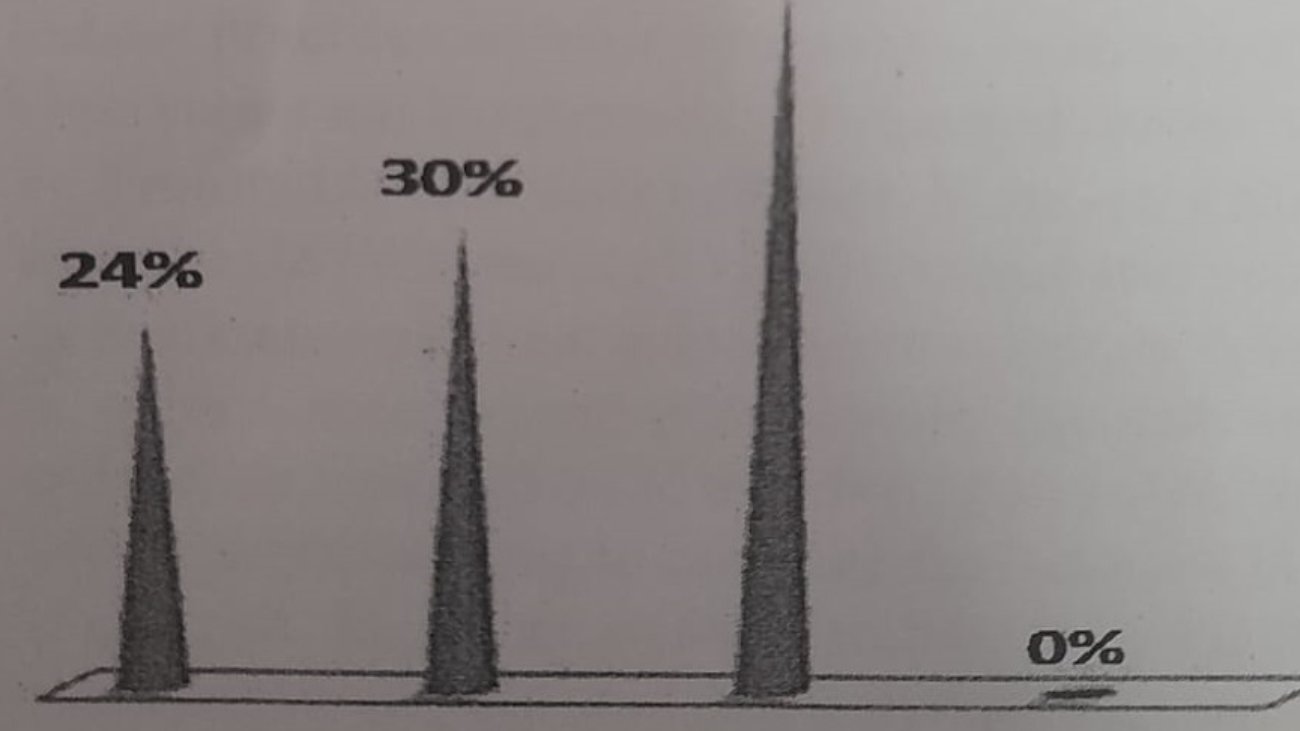

Respondents were asked to give an estimate of the number of visits required to complete the root canal procedures for single-rooted and multi-rooted teeth (Fig. 1).

Radiography:

Majority (89%) of practitioners used conventional radiography techniques whilst 11% take the real time images.

Approximately 81% routinely took pre-

operative radiographs before commencing endodontic treatments, 16% did so occasionally and 3% rarely did so. Sixty three percent of the practitioners took 3 radiographs for routine root canal treatment and 29% took four radiographs contrary to 8% who took only 2 radiographs. However, 72% reported taking master- cone radiograph while 8% taking no radiograph for determining the master apical cone.

Working length determination:

Approximately 40% of respondents obtained working length radiographically, whereas 38% used radiography in conjunction with an electronic apex locator. About 8% relied on tactile sensation. Sixty six percent of respondents took 0.5mm as working distance short of radiographic apex contrary to 30% which took 1-2mm short of radiographic apex.

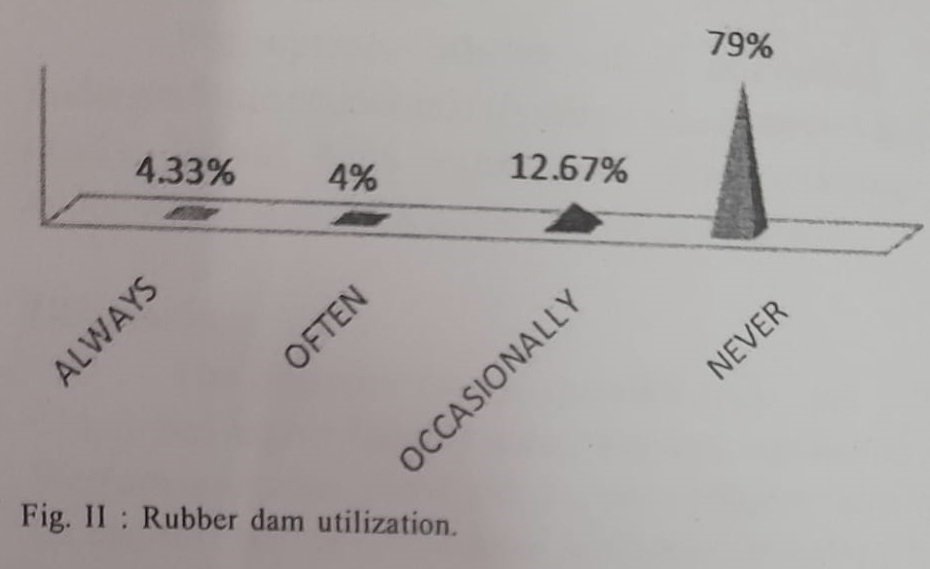

Only (4.33%) of the dentists reported using rubber dam routinely to isolate the field of operation during root canal therapy. The majority (95.67%) were infrequent or non-users of rubber dams (Fig. II).

Instrument selection, technique and maintenance:

For locating the canal orifices, endodontic explorer were used by 18% respondents, on contrary to 36% that never used it. Magnifying loupes or operating microscope is occasionally used by 26% while 72% never used them.

For root canal preparation and debridement, 56% used stainless steel hand files and about 15% reported using rotary nickel-titanium instruments. K- files followed by broach were the most popularly used first instrument in the canal (29%). Golden medium files were not used by 94% of the respondents; 66% never used Gates-glidden. Disposal of the endodontic files after single use was practiced by 2% only. Endodontic files were re-used after sterilization with either autoclaves (33%) or cold disinfection (27%) or by glass bead sterlizer (39%).

The majority of dentists (59.66%) instrumented the canal using the step back technique followed by crown down technique (23.66%).

Root canal irrigants:

Many respondents indicated that they used more than one irrigating agent. Sodium hypochlorite and normal saline solutions were the most popular agents, used by 52% and 24.66% respectively. The most popular concentration of sodium hypochlorite was 2% which was used by 44% of the respondents. Other less commonly employed irrigating agents were hydrogen peroxide (4.83%), ethylene diamine tetra acetate (EDTA) (3.16%), and chlorhexidine solutions by (15.32%; Table IV).

Inter-appointment dressing:

About 74% of employed intracanal medicaments for multi-visit treatments. The remaining 26% usually left root canal space unfilled. The medicaments of choice for both vital teeth and necrotic teeth conditions are shown in Table IV. The most common medicament used was tricresol formalin (51%), followed by non-setting calcium hydroxide paste (23%). Root canal treated tooth is infra-occluded by majority of practitioners (90%).

Obturation technique and materials:

Either cold or warm lateral condensation of gutta-percha with a root canal sealer was used by 91%; others less popular options included warm vertical condensation, thermo-plasticized gutta-percha techniques such as ThermaFil system, continuous waves of condensation technique, Obtura II injectable Gutta-Percha System and a silver-point technique (9%).

The majority of dentists reported the use of a zinc oxide based sealer with the gutta-percha points (55%) followed by a calcium hydroxide based sealer (32%) and resin based sealer(13%; Table V).

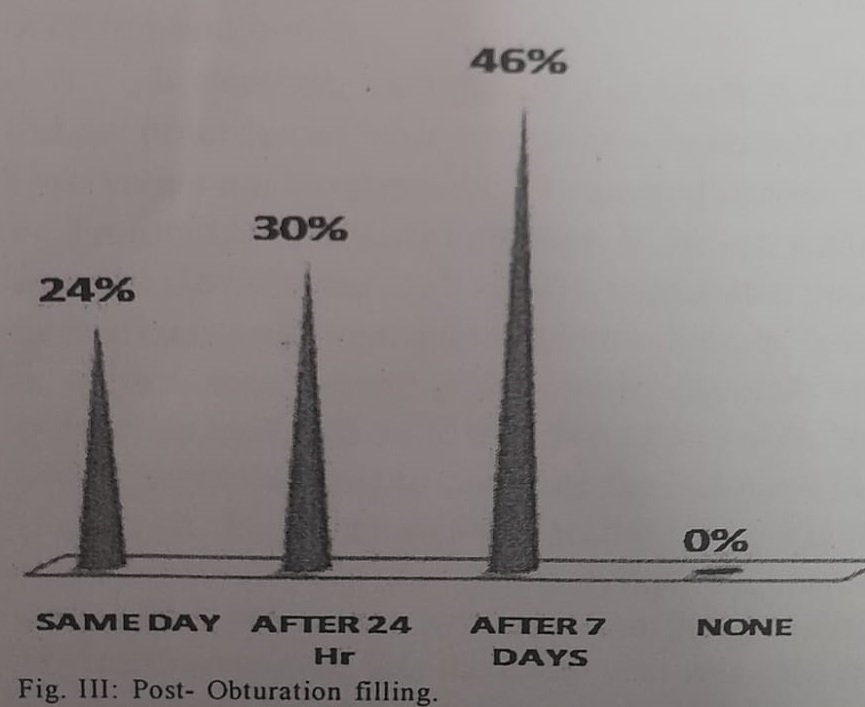

Zinc oxide eugenol cement was the most commonly placed temporary filling (57%) followed by Cavit (27%), IRM(10%) and GIC (6%). Dentists reported using amalgam(32%), composite(36%) and GIC(27%) for posterior teeth and composite for anterior teeth as a permanent coronal restorative material (Table IV). Forty six percent of the respondents preferred to wait for 1 weeks after obturation before placing the permanent coronal filling, whilst the remainder placed the restoration immediately (24%) or after one day(30%) of completion of the treatment (Fig. III).

Post-endodontic prosthetic rehabilitation was preferred by 46% after one week, 12% after 14 days, 40% after 21 days and 2% never adviced prosthetic rehabilitation.

Use of systemic antibiotics:

Antibiotics were prescribed for various clinical conditions. Thirty four percent always prescribe antibiotics in conjunction with endodontic therapy whilst, 62% frequently prescribed them. On the contrary to 4% who never prescribed the use of systemic antibiotics.

Endodontic trainings:

Perception about the adequacy of undergraduate endodontic trainings was obtained in this study. About 92% expressed that training in endodontics was inadequate during graduations.

Discussion:

The response rate to questionnaire was 67% which was higher than in many surveys conducted in Western countries. Now a days, endodontic treatment for single rooted or multirooted teeth are conventionally done in a single visit.

In contrast, vast majority of the respondents did not practice single visit root canal treatment. This observation was in agreement with the study undertaken by Tronstad et al (2000) in Sudan. However, a study from the US (Whitten et al, 1996) demonstrated a clear inclination to single visit endodontic treatment, especially in cases without apical periodontitis. Multiple visit endodontic treatment could be a direct result of lacking adequate clinical time to complete the treatment in a single visit. They may prefer to wait till the complete subsidence of pain and other symptoms before obturating the canal system. Another possible explanation could be that the initial visit was used for treating the pain and acute symptoms.

High quality radiographs had been suggested for accurate diagnosis and pre-operative assessment of potentially difficult case to enable appropriate case selection (ESE, 1944). Besides, this pre-operative evidence also constitutes an important dental record. Despite its importance, only about 81% of the surveyed GDPs routinely examine pre-operative radiographs.

The purposes of rubber dam protection are two- fold; primarily to reduce the risk of foreign body inhalation or ingestion by the patient and secondly to provide an aseptic environment for endodontic procedures. Root canal treatment without a rubber dam can be hazardous and is legally indefensible, should aspiration of an instrument occur. In the present study, 79% of GDPSS never used rubber dam and 12.7% used it occasionally in the practice. Tronstad et al (2000) also found low rate (2%) of use of rubber dam in their study. Similar observation were made by Flemish dentists Friedman (2002) & Kirkevang et al (2000). However, 59% of American dentists (Friedman, 2002), 60% of dentists in UK (Whitworth et al, 2000) and 57% of GDPs in New Zealand (Jenkins et al, 2001) reported using rubber dam routinely in endodontic treatment. Furthermore, many dentist use sodium

hypochlorite irrigation without a rubber dam, despite knowing that irrigant being caustic and distasteful. Although rubber dam isolation is taught as mandatory during undergraduate training, its importance appears to be ignored by GDPs. Practitioners may equate rubber dam use with the extra cost, additional time, lack of adequate skills or training and absence of patient’s acceptability.

In a tooth with an acute pulpitis, the majority of the practitioners perform pulpectomy, while 20% only prescribed analgesics and antibiotics with an acute apical periodontitis without any root-canal instrumentation. It may be that the GDPs’ believe that this condition is associated with difficulty in obtaining a satisfactory level of anaesthesia and was the reason they did not carry out any active treatment.

Working length determination is one of the most critical step in endodontics as it facilitates cleaning, shaping and obturation of the root canal system (Weine, 1996). Failure to accurately determine the length of the root canal often results in apical perforation; overextension of irrigants or obturation materials into the peri-radicular tissues, may also lead to incomplete instrumentation and obturation. A majority of the respondents were using the radiographs to determine the working length. This method has inherent inaccuracy, as the apical foramen may not be detectable on radiographs (Olson et al, 1991). Electronic apex locators (EAL) have the advantage of being able to locate the apical foramen (Pagavino et al, 1998; De Moor et al, 1999). Nevertheless, EAL not a substitute for radiographs since the latter provide valuable supplementary information about root canal morphology as well as peri-radicular anatomy. It, therefore, seems logical to combine the use of EALs with radiographs to enable an efficient and accurate determination of working length. This protocol was actually practiced by about one third of respondents surveyed in this study.

Non-rotary manual endodontic files were commonly used by the GDPs. Recently introduced rotary nickel-titanium files have enabled quicker root canal preparation, as these instruments are able to produce a uniformly tapered canal configuration with minimum canal transportation and also reduce the incidences of peri-radicular irritation and post-operative discomfort (Buchanan, 1996). However, unpredictable instrument separation remains a deterrent to their popularity (Martin et al, 2003). Only about one fifth of respondents were using these rotary instruments in root canal preparation.

Sodium hypochlorite has proven to be a most effective antimicrobial agent, an opinion that is shared by 52% of respondents. The same result was demonstrated amongst dentists in Switzerland (Gatewood et al, 1990), because of its effective antimicrobial and tissue solving action (Pitt Ford, 1983). Many clinicians prefer diluted concentrations of sodium hypochlorite because of its irritant action.

The step back technique was the most popular canal preparation technique among general dental practitioners. The conventional (push-pull) technique, on the other hand, was used by 12.66% of the respondents. Sixty percent of Flemish dentists used the standard filing technique (Qualtrough et al, 1999). Generally, dentists use hand instruments and were not inclined to use more advanced engine driven techniques for shaping the root canal system.

Despite the fact that calcium hydroxide is recognized as the standard intracanal medicament for inter-appointment dressing (Slaus et al, 2002), it was used by only 23% of the respondents. Half of GDPs used formaldehyde containing materials. This finding is consistent with the findings of Tronstad et al (2000). Although formaldehyde containing products have been used for their antimicrobial and fixative properties, they are toxic to periradicular tissues and may have mutagenic and carcinogenic potential (Slaus et al, 2002). The use of calcium hydroxide, as intracanal medication, should be encouraged among dentists, as it is effective against most root canal pathogens, control pain, reduce inflammation, and dry wet canals (Bystrom et al, 1985). Root canal obturation serves to prevent the ingress of microorganisms into the already cleaned root canal system. Majority of the GDPs use cold lateral compaction of gutta-percha to obturate the root canal space. Dentists are not strong advocates of the more recently introduced advanced obturation techniques. This may be attributed to additional cost involved or the lack of skill and training.

According to ESE (1994) guidelines, sealers should be biocompatible. It was found out that most private practitioners used non-medicated zinc oxide- eugenol root-canal cements.

Temporary restorative materials used in endodontics must provide a high quality seal of the access preparation to prevent microbial contamination of the root canal. Twenty-seven percent of the respondents use Cavit as temporary filling material, which under experimental conditions provided superior resistance to bacterial leakage (Beach et al, 1996).

Systemic antibiotics are indicated only if there has been systemic spread of infection. Otherwise, they may present more of a risk to the patient than the local infection. There is evidence that antibiotics are prescribed inappropriately in general dental practices (Palmer et al, 2000). Recent reviews revealed that systematic antibiotics alone offer no additional benefit in the management of acute apical periodontitis and acute abscesses in permanent dentition (Mathews et al, 2003). With the increasing worldwide problem of antimicrobial resistance, there is a need to rationalize prescription of antibiotics.

Conclusions:

Endodontics is a dynamic, evolving discipline with considerable advances in techniques and materials over the last decade. The present small-scale study may not necessarily represent the true picture, however, it can be used as reference for a larger survey in the future.

This study demonstrated that dentists performed procedures which often deviated from well acknowledged endodontic quality guidelines and is often in general practice carried out under less than optimal conditions.

This survey shows the importance of establishing higher specialist training or continuing dental education for practitioners to update their knowledge. There is a need to promulgate the latest concepts and practices of endodontics not only for the undergraduate students but also for general dental practitioners.

References:

1. Al-Omari WM: Survey of attitudes, materials and methods employed in endodontic treatment by general dental practitioners in North Jordan. Bio Medical Central, Oral Health, 2004;4:1

2. Beach CW, Calhoun JC, Bramwell JD, Hutter JW, Miller GA: Clinical evaluation of bacterial leakage of endodontic temporary filling materials. Journal of Endodontics, 1996; 22(9): 459-462.

3. Buchanan LS. The art of endodontics: files of greater taper. Dentistry Today, 1996;15:42,44-46,48-49.

4. Bystrom A, Claesson R, Sundqvist G: The antibacterial effect of camphorated paramonochlorophenol, camphorated phenol and calcium hydroxide in the treatment of infected root canals. Endodontic & Dental Traumatology, 1985;1(5):170-175.

5. Chan AWK, Low D, Cheung GSP, Ng RPY: A 20. questionnaire survey of endodontic practice profile among dentists in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Dental Journal, 2006;3(2):80-87.

6. De Moor RJG, Hommez GMG, Martens LC, De Boever JG: Accuracy of four electronic apex locators: an in vitro evaluation. Dental Traumatology, 1999;15(2):77-82. 7.

7. European Society of Endodontology: Consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology on quality guidelines for endodontic treatment. International Endodontic Journal, 1994;27(3):115-124.

8. Friedman S: Considerations and concepts of case selection in the management of post-treatment endodontic disease (treatment failure). Endodontic Topics, 2002;1(1):54-78.

9.Gatewood RS, Himel VT, Dorn SO: Treatment of the endodontic emergency: a decade later. Journal of Endodontics, 1990;16(6):284-291.

10. Jenkins SM, Hayes SJ, Dummer PM: A study of endodontic treatment carried out in dental practice within the UK. International Endodontic Journal, 2001;34(1):16-22

11. Kirkevang LL, Ørstavik D, Hørsted-Bindslev P, Wenzel A: Periapical status and quality of root fillings and coronal restorations in a Danish population. International Endodontic Journal, 2000;33(6):509-515.

12. Martin B, Zelada G, Varela P, Bahillo JG, Mogan F, Ahn S, Rodriquez C: Factors influencing the fracture of nickel-titanium rotary instruments. International Endodontic Journal, 2003;36(4):262-266.

13. Matthews DC, Sutherland S, Basrani B: Emergency management of acute apical abscesses in the permanent dentition: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Canadian Dental Association, 2003;69(10):660.

14. Olson AK, Goerig AC, Cavataio RE, Luciano J: The ability of the radiograph to determine the location of the apical foramen. International Endodontic Journal, 1991;24(1):28-35.

15. Pagavino G, Pace R, Baccetti T: A SEM study of in vivo accuracy of the Root ZX electronic apex locator. Journal of Endodontics, 1998;24:438-441.

16. Palmer NA, Pealing R, Ireland RS, Martin MV: A study of therapeutic antibiotic prescribing in National Health Service general dental practice in England. British Dental Journal, 2000;188(10):554-558.

17. Pitt Ford TR: The practice of endodontics by different groups of dentists in England. International Endodontic Journal, 1983;16(4):185-191.

18. Qualtrough AJ, Whitworth JM, Dummer PM: Preclinical endodontology: an international comparison. International Endodontic Journal, 1999;32(5):406-414.

19. Slaus G, Bottenberg P: A survey of endodontic practice amongst Flemish dentists. International Endodontic Journal, 2002;35(9):759-767.

20. Tronstad L, Asbjörnsen K, Doving L, Pedersen I, Eriksen HM: Influence of coronal restorations on the periapical health of endodontically treated teeth. Endodontic & Dental Traumatology, 2000;16(5):218-

21. Weine FS: Calculation of working length. In: Endodontic therapy. 5h Edn.; Mosby, St. Louis; 1996:395-

22. Whitten BH, Gardiner DL, Jeansonne BG, Lemon RR: Current trends in endodontic treatment: report of a national survey. Journal of the American Dental Association, 1996;127(9):1333-1341.

23. Whitworth JM, Seccombe GV, Shoker K, Steele J G: Use of rubber dam and irrigant selection in UK general dental practice. International Endodontic Journal, 2000;33(5):435-441.

Interesting points! Managing risk is key, and tools like an AI Video Generator can help creators quickly test content ideas. Accessibility across devices is a huge plus for fast iteration & analysis!

Scratch cards are such a fun, quick thrill! Thinking about creative content, I recently discovered how easy it is to generate visuals – even with something like Sora 2. It’s amazing how accessible AI tools are becoming, working on any device!

Love playing on 80jiliph. So many choices. Lots of fun experiences here. Good stuff! Feel the enjoyment here: 80jiliph

Yo, TBJILI is my go-to spot! Always got the newest games and the bonuses are legit. Been cashing out pretty regularly, no cap. Check it out tbjili, you might get lucky too!

Just stumbled upon fortunemouse4 and gotta say, I’m impressed. The site is slick and easy to navigate. Looking forward to seeing what else they have to offer! Check it out fortunemouse4, you might just get lucky.

Bet188link, đường dẫn mới của 188bet hả? Mấy cái link này hay bị chặn lắm, phải có cái dự phòng thế này mới yên tâm được. Thanks for sharing bet188link.

I am thanksful for this post!

188bethiphop? That’s a wild combo! Hip-hop theme with betting? Interesting. I’m intrigued. Def gonna check it out and see how they roll. 188bethiphop

Yo, just tried out PHDream11login. Pretty smooth experience overall! Def a solid choice for getting your game on. Check it out here: phdream11login

Heard some buzz about the Pagcor Portal. Gotta say, it’s pretty handy for keeping up with things. Worth a look, peeps! More info here: pagcor portal

ph789 login https://www.ph789-login.com